Unveiling the Rich Cultural Tapestry of the Cordilleras

The moment I stepped through the doors of the Baguio Museum, I felt as though I was being transported into the heart of the Cordilleras. The museum, though modest in size compared to grand city museums, is bursting with a wealth of history and culture that feels almost palpable in the air. From the exterior, the building itself is unassuming, yet its simplicity reflects the understated charm of Baguio, the city known for its cool climate and pine-scented air. However, what awaited inside was far from simple.

As I entered, I was greeted by a large open gallery that immediately commanded attention with its vibrant display of artifacts from various indigenous tribes of the Cordillera region. The museum’s layout was well-organized, with sections devoted to different aspects of life in the highlands. The first exhibit I encountered was a tribute to the various ethnic groups that make up the fabric of this region—the Ifugao, Kankana-ey, Ibaloi, Bontoc, and Kalinga, among others. Large panels of text offered insights into their unique languages, customs, and beliefs. It was fascinating to learn that each tribe, while distinct in its traditions, shares a deep-rooted connection to the mountainous terrain they inhabit.

The showcase of traditional attire immediately caught my eye. Encased in glass, these colorful garments were beautifully preserved, representing the high level of skill and artistry involved in their creation. The handwoven textiles, with their intricate patterns and vibrant colors, spoke of a deep connection to nature. The textiles often used symbols that represent rice terraces, rivers, and mountains—landforms that have played crucial roles in the lives of the Cordilleran people for centuries. As I examined the detail, I imagined the countless hours of labor and dedication required to weave such masterpieces on backstrap looms, a method still practiced today.

Near the clothing exhibits were displays of traditional jewelry, often made from brass, silver, beads, and sometimes gold. The pieces were not just ornamental but often carried spiritual and social significance. I learned that certain accessories were worn only by the elite or those who had achieved great feats, such as headhunters. These tokens of achievement and status stood as reminders of the complex social hierarchies and belief systems that governed Cordilleran life.

One of the most captivating sections of the museum was the collection of wooden carvings and ritual objects. The wooden sculptures, often referred to as "Bulul," represent rice gods. These statues were crucial in agricultural rituals, believed to ensure the fertility of the crops and the prosperity of the community. The Bulul, with their stoic expressions and simple postures, conveyed a sense of reverence and continuity, as though their quiet presence had watched over generations of Cordillerans. I found myself reflecting on the deep spiritual connection these tribes had with their land—a relationship of mutual respect, where the earth was not merely a resource to be exploited but a sacred space that sustained life.

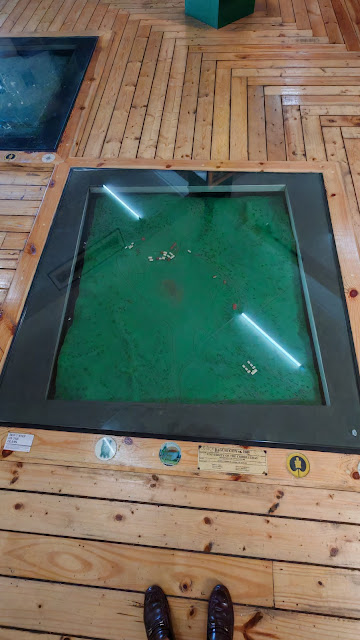

Continuing my journey, I came across one of the most unique displays—the miniature traditional houses of the Cordilleran tribes. These models, constructed with careful attention to detail, provided a fascinating glimpse into the indigenous architecture of the region. Each tribe’s house had its own distinct design, yet they all shared an ingenious simplicity, utilizing materials like bamboo, cogon grass, and wood. The Ifugao house, for example, was elevated on stilts with a thatched roof, designed to withstand the region’s frequent rains and cool climate. Inside these dwellings, families lived communally, cooking over open fires and sleeping in close quarters. It was hard not to admire the resourcefulness of these structures, which were built with materials sourced entirely from the surrounding environment.

The houses were not just shelters but held significant cultural meaning. The placement of objects within the home, the way the house was oriented in relation to the mountains, and even the way food was stored spoke volumes about the spiritual beliefs and daily practices of the people who lived there. The designs also reflected their deep understanding of the natural world, from the rugged topography to the seasonal patterns of rain and sun.

As I moved further into the museum, I found a section dedicated to musical instruments. The Cordilleran people, much like other indigenous groups across the Philippines, have a rich tradition of music and dance. Displayed in this section were gongs of various sizes, flutes, and bamboo instruments, all of which have been used for centuries in communal celebrations, rituals, and storytelling. I was particularly drawn to the gangsa, a type of flat gong that is central to many Cordilleran ceremonies. These instruments were not merely for entertainment; they were a means of communication with the spiritual world, used to call upon ancestors or to express gratitude for bountiful harvests.

The accompanying audio-visual displays allowed me to listen to the hauntingly beautiful rhythms that these instruments produced, filling the air with a sense of mystery and spiritual energy. In my mind, I could imagine the vibrant gatherings of villagers, the rhythmic movements of their dances, and the echoing beats of the gongs as they celebrated life, death, and the cycle of seasons. It was a stark reminder of how closely intertwined their music, dance, and rituals were with their everyday lives and their connection to nature.

The museum also highlighted the historical context of Baguio City and the Cordilleras. One wing was dedicated to Baguio’s colonial past, particularly its transformation during the American occupation of the Philippines in the early 20th century. Photos from that era depicted Baguio as the summer capital of the Philippines, where American architects like Daniel Burnham had designed urban plans that incorporated parks, wide roads, and scenic views to take advantage of the city’s cool climate. This section was filled with photographs of Burnham Park, Baguio Cathedral, and the famous Kennon Road, which was an engineering marvel at the time, connecting the mountainous city to the lowlands. These photos provided a glimpse into the blending of indigenous cultures with colonial influences, a process that shaped Baguio into the cosmopolitan city it is today.

Another wing showcased World War II memorabilia. Baguio, being a strategic location, played a pivotal role during the war, and the museum did well to honor this chapter of history. Exhibits featured military uniforms, weapons, and documents, alongside images of the city in ruins after bombings. One of the most poignant sections was the documentation of the Filipino and American soldiers who fought in the area and the resilience of the local population during the war years. It was a sobering reminder of the turbulent history that shaped not only Baguio but the entire country.

As I reached the final section of the museum, I was drawn to a display that focused on modern Baguio and the ways in which the city has adapted to changing times while still holding on to its cultural roots. This exhibit showcased contemporary works of Cordilleran artists and designers, many of whom are finding innovative ways to merge tradition with modernity. The vibrant tapestries and paintings on display reflected themes of identity, land, and resistance, as these artists grapple with the challenges of preserving their heritage in a rapidly globalizing world.

By the time I concluded my visit, I felt a deep sense of respect and admiration for the Cordilleran people. The museum, while not large, managed to convey the immense richness of their culture, the resilience of their traditions, and the importance of their connection to the land. It was a humbling experience to walk among the artifacts that had borne witness to centuries of history, to learn about a way of life that, though evolving, remains deeply rooted in the mountains of the Cordilleras.

Leaving the museum, I stepped back into the cool air of Baguio, but my mind was still filled with images of rice terraces, ritual dances, and the steady gaze of the Bulul statues. The visit had been more than just an educational experience; it had been a journey into the soul of the highlands—a reminder that even in our fast-paced modern world, there are cultures that continue to honor and preserve their ancestral ways. As I walked away, I promised myself to return, not just to the museum but to the Cordilleras themselves, to experience firsthand the landscapes and people who had shaped this rich cultural heritage.

Comments

Post a Comment